SPOTLIGHT FEATURE - October, 2016

Swimming with Sharks, Climbing El Capitan, Flying through the Air and Other Adventures

REPORTERS: Aiden Ament, Sabrina Chafee, Kylar Flynn, Katrina Horsey, Ellie Jenkins, Parker Kulavic, Jessica Le, Jane Merkle, Rachel Metzger, Will O’Hara, Elliott Soofer, Lyle Rumon, Christine Watridge, Sari Wisoff FROM: Branson, Home-School, Marin Academy, Marin Catholic High, Marin Country Day School, Marin Waldorf, Novato School of the Arts, Redwood High, Tamalpais High, Terra Linda High Schools

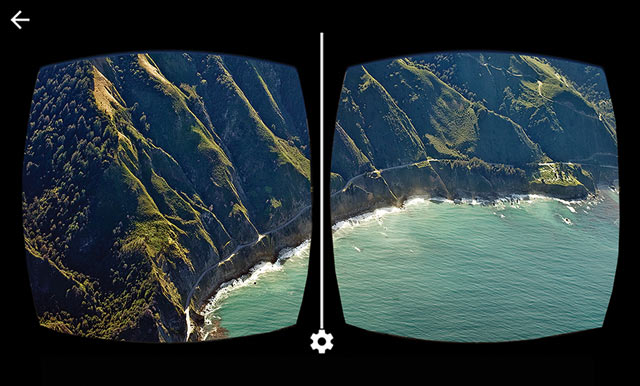

We could feel our feet on the floor and our hands gripping the edge of the table in front of us. We knew we were safe, perched on black mesh swivel chairs in a conference room walled by whiteboards and carpeted in blue. But our sight deceived us. Because when we looked down, thousands of feet of empty space plunged past where our feet should have been and a lush forest sloped for miles in every direction. We were teetering in perilously mid-air, barely secured to El Capitan, Yosemite’s imposing 3,000-foot sheer vertical wall of granite, by a measly rope and harness. Was this reality? Yes, virtual reality. Brought to us—all of us—by Google.

As FastForward reporters, we had the opportunity to meet with the leaders of Google’s virtual reality (VR) team and learn about the cutting edge developments in this exciting area of technology. The Google VR team encompasses products including Cardboard, Daydream, Expeditions, and beyond. Mike Alemeris, Strategy and Ops Lead for Google Cardboard and Ben Schrom, Leader of Google Expeditions led us on a journey through the dreaming, doing and designing it takes to make virtual reality an everyday reality.

Ben started us off. “I was just in Yosemite this past weekend,” he explained. “It is amazing and I’d love to be a rock climber, but I’m not a rock climber.” He paused, dramatically. “So... I thought maybe we would go rock climbing today.” He led us on an experiment with Google Cardboard, its simple exterior modestly hiding whole worlds inside. “It used to take people just days and days and days — months, even — to climb El Capitan. The first ascent took 18 months. Lynn Hill was the first one to do it in less than a day, and now she can do it in just a few hours. So we’re going to climb with her.” Although physically Cardboard is nothing more than a piece of cardboard with two lenses and a magnet, when we held it up to our eyes, suddenly right before us appeared the majestic El Capitan in all its glory. The imagery was outstanding, creating a true unparalleled experience. We were stunned to learn that Google has more than 250 “locations” like this available to explore now.

“We’ve taken [Cardboard] to schools in 11 countries, over a million students, and the number one thing that people like to see?” Ben intoned, catching our attention. “Sharks.” Never the kind of people to be deterred by a challenge, the Google VR team asked how they could bring a shark-infused undersea adventure to the land-based world. Like many, they weren’t particularly fond of swimming with sharks. So, they partnered with a company called Catlin Sea Survey that specializes in underwater video footage. “They’re a bunch of Australian guys who live underneath the water,” describes Ben.

And, voilá: an underwater world is available in virtual reality on Cardboard, sharks and all.

There are now more than six million Cardboard VR systems in circulation all over the world. But how did we get here? Two years ago, companies like Sony, HTC and Oculus were releasing VR equipment, “but they were doing it for a very small group of people,” explains Mike. In order to run those machines, you needed not only the VR platform itself, but also a powerful computer costing several thousand dollars to enable the processing, significant physical space, and a high level of technical knowhow. Google imagined a world where many more people could access this technology. “At Google we deal in the billions, not in the thousands,” says Mike, “so we wanted everybody to have an opportunity to access VR and the content that could come along with it,” such as educational materials, entertainment, movies, gaming, transportation, and more.

Thus the Google VR story began, as Mike tells it, with “two engineers in a Paris hotel room in May of 2014.” The two sat down and thought about how to bring VR to everyone. The answer quickly became clear: cell phones. “5.5 billion people in this world have a phone. That’s more than actually have a computer,” says Mike. “So we used the phone as the vehicle to drive the VR experience. Then [the question was], how do you create immersion with the phone? So they used a piece of cardboard, those two lenses, and that magnet we talked about and put the phone inside the box to give you a snackable VR experience.”

Cardboard is handheld; there’s no way to simply secure it on and walk around. The lack of a head strap facilitates a high quality visual experience. With VR, we learned, there’s an important issue nick-named “MOPHO,” for motion-to-photon latency. Motion-to-photon latency “is all about the display on your phone catching up with your movements. An older phone isn’t going to be able to catch up as fast, and so while you move this way and you have a head strap on, you can really whip your head that way,” demonstrates Mike. Since “the display actually won’t catch up with your head moving in that direction, it’s going to make you really sick.” Cardboard avoids that.

Cardboard is handheld; there’s no way to simply secure it on and walk around. The lack of a head strap facilitates a high quality visual experience. With VR, we learned, there’s an important issue nick-named “MOPHO,” for motion-to-photon latency. Motion-to-photon latency “is all about the display on your phone catching up with your movements. An older phone isn’t going to be able to catch up as fast, and so while you move this way and you have a head strap on, you can really whip your head that way,” demonstrates Mike. Since “the display actually won’t catch up with your head moving in that direction, it’s going to make you really sick.” Cardboard avoids that.

“There’s no head strap, so unless you’re a muscle man who can hold sandbags for hours it’s probably going to be a limited experience for five minutes,” explains Mike. “But what’s great about it is it’s really social, it’s not isolating and it’s easy for you to watch or engage with a piece of content and then hand it over to a friend who can do the same thing.”

Ben adds, at Google, “We’re really into saying that’s not a bug, that’s a feature. And in this case it’s really true.”

The next step in Google’s VR experiment is called Daydream. Daydream is a head-mounted display that will come with a controller. The team recently announced it at I/O, Google’s developer conference held at Shoreline Ampitheater in Mountain View. The conference represents a major moment for sharing information and announcing new projects. The name itself is significant: the “I” and “O” in the name stand for input/output, as well as the slogan “innovation in the open,” according to Wikipedia. Since this new technology also utilizes the power of cell phones, and cell phone manufacturers need time to catch up to the quickly changing environment, the whole system will actually be available in the fall of 2016: according to Mike, “Daydream-ready phones are going to launch this fall and then we will launch alongside that with this new headset and controller bundle.”

Whereas Ben focuses on the business and operations side of things, Mike is one of the team’s product managers and describes his role as “represent[ing] the voice of the user for engineers.” A self-described “gamer at heart,” Mike says that “gaming is one of the key verticals that’s going to be affected by VR, and will evolve how we game.” His work involves becoming intimately familiar with VR in gaming. He described his recent attendance at the Electronic Entertainment Expo, or E3, the annual video game conference and show at the Los Angeles Convention Center, as “three days just playing games in VR for PlayStation and Oculus.” His favorite VR games? For multi-player, he describes Eagle Glide by Ubisoft as “a really cool social experience where you’re all eagles, you’re trying to get the food first and you’re on teams, so it’s kind of like Capture the Flag.” Visually, he says, “The new Zelda by Nintendo is graphically one of the most insane games I’ve ever seen.”

Ben describes the relationship between Google and rival VR companies as productive. “It’s like there’s a competitive aspect there, but there’s also so much mutual appreciation and building on each other,” he says.

As much as it seems the field is developing, VR is really still in its beginning phases. Google’s VR team started with a staff of two in 2014, and now reaches near 200 employees. The work of the Daydream team is in part to imagine and create the next frontier in VR. Ben explains that they’ve been doing a lot of thinking about how people can connect within VR. “There’s something that is really important about actually being next to somebody. Think about eye contact. When I’m talking to you guys, we’re looking in each other’s eyes. If you’re like this [with Cardboard on your face], it’s really hard to make eye contact, right? It’s going to take a lot of technology to figure out how to make eye contact with somebody whose eyes are occluded, covered up,” he says.

It’s easy to see Mike and Ben’s eyes light up when they describe the potential futures for VR. They bounce ideas back and forth off each other at light speed: Experiencing the universe of a refugee camp. Constructing art. Test-driving cars. Viewing the world from the eyes of someone who’s colorblind. (Per Mike: “I’m colorblind. You don’t want to be colorblind. I’m ust going to put it out there.”) Remote college campus visits. Watching movies with friends who live far away. Breaking down physical barriers.

It’s easy to see Mike and Ben’s eyes light up when they describe the potential futures for VR. They bounce ideas back and forth off each other at light speed: Experiencing the universe of a refugee camp. Constructing art. Test-driving cars. Viewing the world from the eyes of someone who’s colorblind. (Per Mike: “I’m colorblind. You don’t want to be colorblind. I’m ust going to put it out there.”) Remote college campus visits. Watching movies with friends who live far away. Breaking down physical barriers.

“I want to be on an airplane and I want to be able to put on VR and just look around as if I’m flying through the air without the airplane. I want to be able to look through the floor and see beneath it. I want that,” exclaims Ben. “I want to be able to make a thing in VR and press a button and a 3D printed version of it shows up. Say I want this toy for my kid. I’m just going to make it, boom, print, and then it shows up in plastic. I want to do that.”

What is the result of all of this potential in VR? Maybe, just maybe, greater empathy. As Ben describes, “Understanding someone else’s perspective and their viewpoint? That’s a really important thing to living in the world with other people. With VR, you can literally stand in someone’s shoes. You can understand what it’s like to be someone who’s in a refugee camp or somebody who has colorblindness. All these ways we can use to actually let you figure out what it’s like to be somebody who is in another circumstance. And that, I think, will make the world hopefully a better place.”